Teaching with Films

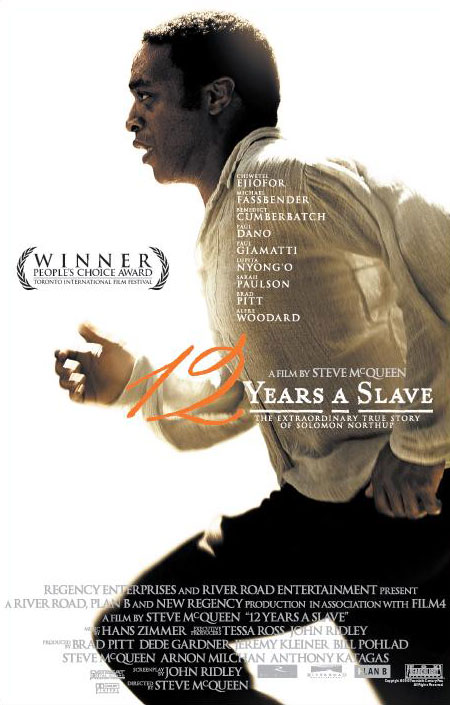

The first time I taught a class on historical memory, or the study of how people remember the past and how history is represented all around us, I made a classic rookie mistake. The class had spent a week reading arguments about the importance of filmed representations of the past, debating how historical films were shaped by genre conventions, and discussing how films make historical arguments and communicate historical information even when they stray from the historical record. We considered the political work done by different ways of telling historical stories, such as by the many films that make white characters the heroes in stories about civil rights. We also explored how films—with their powerful arsenal of sound and visuals—can shape our perceptions of what the past was actually like. They also can  communicate emotion, urgency, and a sense of time and place in ways that can be hard to do in writing. As an assignment, each student had to watch and analyze a film that offered a representation of the past. As soon as I started reading the essays, I realized that I couldn’t actually grade them unless I watched all of the films first. I spent a long week watching sixteen different movies. The following year, we decided that we would all watch 12 Years A Slave together and then each student wrote their own analysis of that powerful film’s representation of a free Black man who is captured and sold into slavery.

communicate emotion, urgency, and a sense of time and place in ways that can be hard to do in writing. As an assignment, each student had to watch and analyze a film that offered a representation of the past. As soon as I started reading the essays, I realized that I couldn’t actually grade them unless I watched all of the films first. I spent a long week watching sixteen different movies. The following year, we decided that we would all watch 12 Years A Slave together and then each student wrote their own analysis of that powerful film’s representation of a free Black man who is captured and sold into slavery.

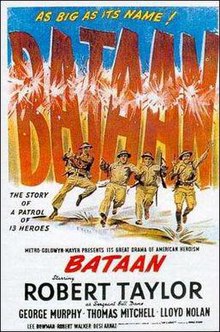

I use films to teach students to interrogate historical interpretations and to examine how historical narratives are constructed. But I also use films as primary sources in nearly all of my classes. Films are rich historical documents that can help us understand the politics, culture, and key concerns of the era in which they were created. My class on the history of US Foreign Policy includes five feature films, each from a different historical era. Mainstream feature films offer a particularly important site for analyzing ideas, values, and cultural beliefs about Americans’ views of their place in the world. Films that I’ve taught in that class over the years include Martyrs of the Alamo, a film from 1915 which we analyze not as a source about what happened at the Alamo, but as a primary document that illuminates attitudes  towards American empire in the early the 20th century; All Quiet on the Western Front (1930), a great source for understanding how WWI contributed to anti-war sentiment; Casablanca (1942); The Manchurian Candidate (1962); Top Gun (1986); and Zero Dark Thirty (2012). In my class on World War II, students analyze the 1943 film Bataan as a film that helped maintain American morale despite early losses in the war. They watch Best Years of Our Lives (1946) as part of our exploration of Americans’ anxieties about the postwar world and about the reintegration of soldiers back into civilian life.

towards American empire in the early the 20th century; All Quiet on the Western Front (1930), a great source for understanding how WWI contributed to anti-war sentiment; Casablanca (1942); The Manchurian Candidate (1962); Top Gun (1986); and Zero Dark Thirty (2012). In my class on World War II, students analyze the 1943 film Bataan as a film that helped maintain American morale despite early losses in the war. They watch Best Years of Our Lives (1946) as part of our exploration of Americans’ anxieties about the postwar world and about the reintegration of soldiers back into civilian life.

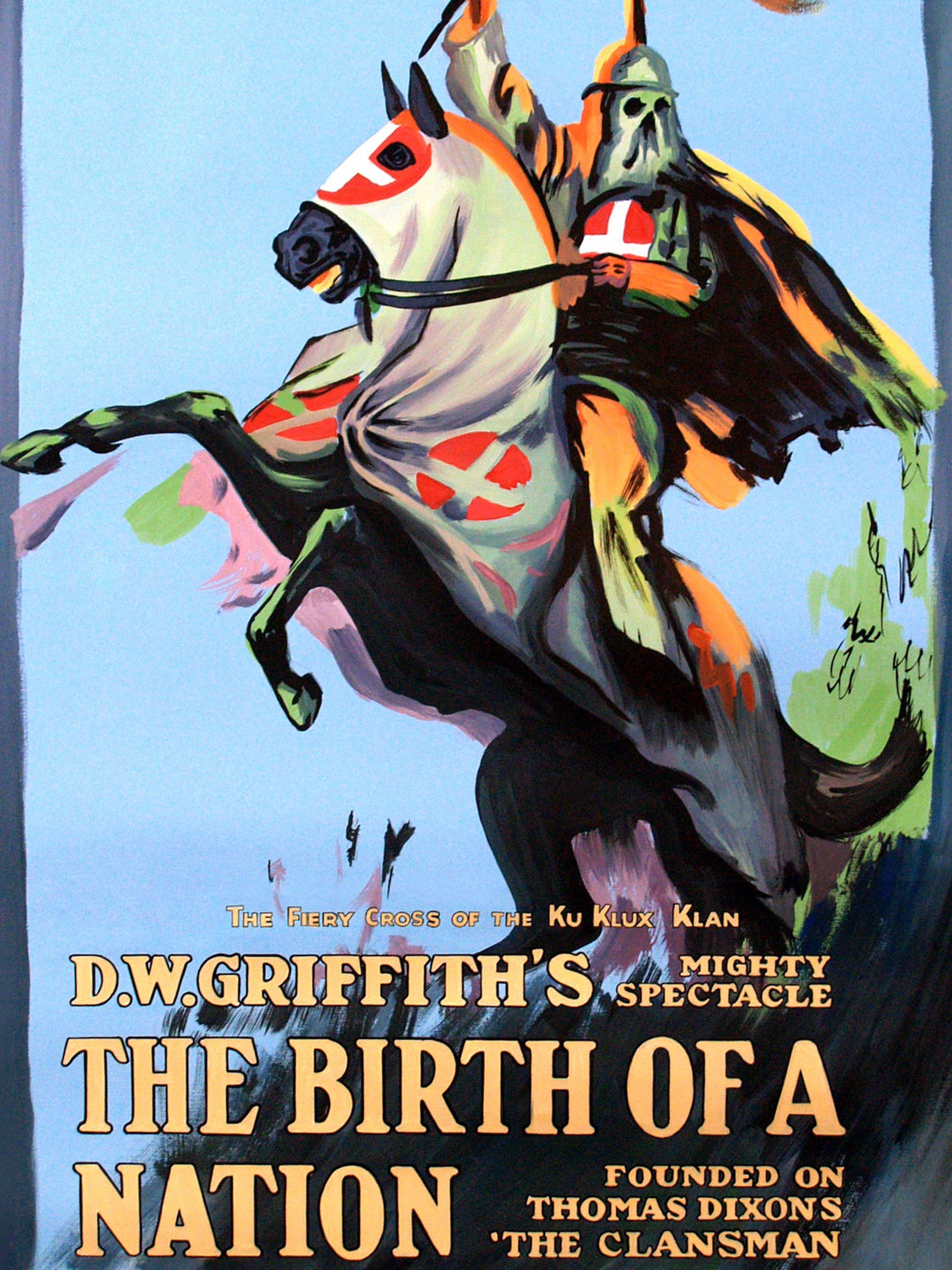

Films can also be powerful historical forces in their own right and my teaching also highlights films that have had significant historical legacies. As painful as it is to watch, I make students in my History of Whiteness class sit through most of the 1915 film, Birth of a Nation. That film, which portrays the Ku Klux Klan as heroes saving the white South from the horrors of Reconstruction and black political rule, had a huge impact at the time it was released. In later years, it has continued to popularize the “Lost Cause” narrative of the Civil War and Reconstruction.

Films can also be powerful historical forces in their own right and my teaching also highlights films that have had significant historical legacies. As painful as it is to watch, I make students in my History of Whiteness class sit through most of the 1915 film, Birth of a Nation. That film, which portrays the Ku Klux Klan as heroes saving the white South from the horrors of Reconstruction and black political rule, had a huge impact at the time it was released. In later years, it has continued to popularize the “Lost Cause” narrative of the Civil War and Reconstruction.

Finally, I also use documentaries in my classes, films like I Am Your Negro and The Life and Times of Rosie the Riveter. I try to get students to engage with documentaries as secondary sources that are offering historical interpretations. We explore who made the documentary and when, what evidence the film uses to make its argument, its perspective or point of view, and how it uses historic footage in crafting its narrative.

What I have not explicitly taught yet is digital storytelling, where students use video as a medium to communicate their own historical research. I often have final projects where I allow the students to choose the format in which they want to convey their research, whether that is through a paper, a podcast, a website, an exhibit, or a zine, and as a result, a few ambitious students have done films (one even a stop-motion film about the Rwandan Truth Commission!). But I have not ever required students to make a film or designed an assignment that would support them in learning how to do so. I can see many benefits to teaching students the skills of digital storytelling, however. Making a film requires you to think deeply not only about what your argument is, but about what structure will convey that argument most effectively and which pieces of evidence best illustrate your claims. Digital storytelling demands attention to audience, tone, and clarity (which should also happen when students write papers, but often is not at the forefront of their mind). A film demands some clarity around the “so what” question, or an explanation of why its topic has historical significance. Creating a film which can be easily distributed also, I suspect, may also help students see that their historical work is relevant and timely. I may have to think about designing a new assignment for one of my classes this year….